The Claw

Horrible. Just horrible.

Note: When I started this substack, part of the plan was, from time to time, to take an old, out-of-copyright short story and rework it in a contemporary setting. It’s something I’ve done before, and in the past I found it a fun and satisfying exercise, of the puzzle-solving kind — like transposing a piece of music into a different key, or designing a well-balanced board game. A couple of months ago, I wanted something quick to put out while I edited a big serialised story that’s coming soon, so I thought: I know, I’ll do a remix of The Monkey’s Paw.

The Monkey’s Paw is a classic horror story, a masterpiece of compression with a simple ‘be careful what you wish for’ premise. Like a lot of older horror stories, I find that its power to inflict actual horror has faded with age. I thought I could have fun tweaking things to bring the original horror back into focus. I thought it would be a technical exercise, that would take about a week. Fun and satisfying, like I said.

It took a lot longer than a week, and although I am in fact satisfied with the result, it was not fun. If you read my subtitle for this story (‘horrible, just horrible’) and thought it was in any way jokey, think again. My little tweaks, my technical exercise, followed through to the bitter end, have delivered up what is certainly the most horrible thing I have ever written. My first reader had to skim some of the later sections. The Monkey’s Paw can’t really be said to have a happy ending, but one of my tweaks, the main one I suppose, was to remove whatever sliver of consolation there is at the end of the original. So consider this a trigger warning. I’m serious. I’m not a fan of such things in general, but I can’t bring myself to press ctrl+v without giving you fair warning that this is going to get rough.

Anyway, here goes:

The Claw

This was back in the Covid days. It doesn’t have anything to do with the actual Covid, though, except: if you read this, and think, don’t lie? Remember those days, and now be honest: if I told you all that was going to happen, before it happened, would you not think, don’t lie?

As in, people think: don’t believe crazy shit, and you won’t get mugged? And if you do believe, that makes you a dozy prick? But sometimes: no. Sometimes you don’t believe until it’s too late. More about that later.

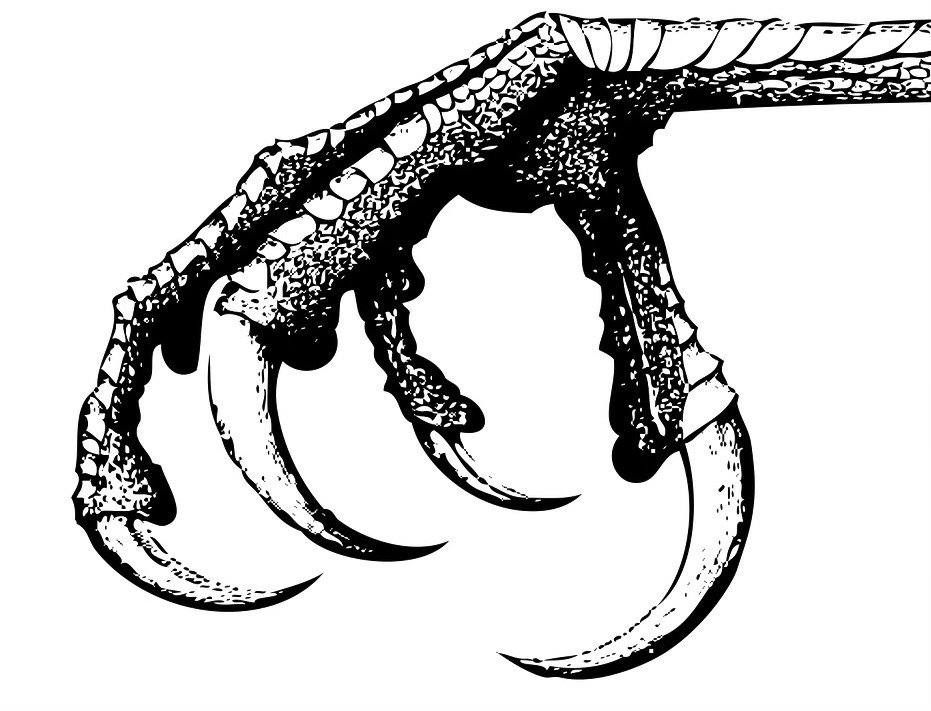

Now I’m on Covid, though: I never made the connection before, but it was a bat claw. That’s what the note said, anyway. It was so manky you couldn’t tell, well I say manky, but the actual claw wasn’t. The actual claw looked shiny and dark like a new phone screen when you’ve just peeled off the plastic cover. But the foot? That was a sorry sight. Foot, paw, I don’t know what you call it when it’s a bat, if it was a bat. It looked like something that had been run over in the road, in the rain, run over a few more times, then just lain there for a month of hot summer days. I’ve seen pigeons that looked like that, and squirrels. Roadkill.

Anyway, I was going to begin with the claw, and then I remembered about the furniture and animal heads, and the sunbathing, but now I think of it that wasn’t the beginning either, or at least if I do start there I’ll have to go back later so I might as well tell you now about the dog — which makes the dog the beginning — and that was right at the start, early Covid, even before the lockdown.

The dog was an American Bully XL. Yeah. I’m guessing you’re not the type of person who has an American Bully, and no way with young kids in the house. You’re probably — here’s a Covid word for you — from the laptop class. We were from the laptop stealing class. Not us in particular, but you’d look at us and that’s what you’d think. And fair enough: that’s what we looked like, and there was enough of that type on the Duchess Estate, which was where we lived.

We didn’t steal laptops in my family though. We were a higher type than that. For example: Uncle Sean, Jude’s dad, back in the 90s, ran a pirate radio station out of his flat, wires all up around the roof to get the broadcasting power. Jungle, garage, anything with a breakbeat basically, and you could pick it up in Romford. So Uncle Sean said, anyway: I don’t know why Romford in particular. Once he started promoting parties, Kenny’s lot got involved selling the pills: so I can’t say he was pure as snow. But a higher level than laptop stealing anyway.

I’m getting away from the dog, although the music thing comes into it too. More about that later, again! But for now back to the dog, and Jodie. Haven’t mentioned her yet.

Jodie. Yeah.

Jodie was my little sister, and she loved that dog from the moment she saw it. Seeing what happened later, you could say she was wrong, silly little girl, should have known better: but I don’t think she was. He was a sweetheart, to tell you the truth. I know what they say about American Bullies but he was: dozy prick of a dog — Bobo — named by Jodie of course, she was the namer in our family, always making up words and names and they were always dead on.

Dad was away then — he’d been looking after a couple of kilos for Kenny, silly cunt had it in the back of his car and got stopped jumping a red — and mum said she’d feel safer with a dog in the place. I don’t know, it’s not like dad was keeping us safe as his number one priority, but anyway the decision turned out good because, once the lockdown came in, we all had an excuse to go outside.

Mad, though, wasn’t it? During lockdown? I remember walking Bobo down Henry Walk, not the street but the park bit on the other side of the posh houses from us, with the little river and trees with the leaves hanging down and park benches — and they’d put police tape over the benches. You know, in case anyone sat down next to anyone else. And along comes this Henry Walk type man, I’d seen him before, had one of those scruffy little terriers that he’d walk along there, always in a suit and tie and a little hat with a feather (the man, I mean). And he sees the tape and starts ripping it off with his walking stick, had a handle made of brass in the shape of a duck’s head. Angry man. Mum was walking Bobo with us that time, and she did a little whoop and said Go, grandad and he took off his hat to her and did an actual bow, like jerking his whole body at the waist, still angry as fuck: red in the face, eyes all shiny and that.

Another one, from dog-walking: that park bit of Henry Walk had just the one path, going along beside the river, and the council made it a one-way system. You had to go in at one end, come out the other, go back home along the street pavement. One time, walking Bobo again, he goes running back the way we’ve come because he’s seen a rat — don’t know why, but there were loads of rats everywhere along Henry Walk that year — and Jodie goes running after him, won’t come back, so mum goes running after Jodie… and this woman, coming along behind us, normal-looking woman with a Sainsbury’s bag, steps out in front of mum and stops her, screaming in her face, like ‘Don’t you care about other people, who do you think you are,’ everything like that. Because she’s going against the one-way system, right? Jodie stopped then, came back shouting at the woman, and when she turned around, Jodie was crying, going leave my mummy alone, Bobo coming up behind, barking his big dopey bark. Sainsbury’s lady didn’t know what to do about that: walked on by, I took two steps out of her way but when she went past me she turned her head at me and hissed, look in her eye like a cat with rabies, if cats get rabies. And then, right, someone had left one of those electric Uber bikes on the path, and that was it for her, she just groaned, I swear, ‘People are so irresponsible!’ and then picked it up, smashed it down on the path so its little kickstand broke off, then threw it in the water.

Mad days.

That year’s all a bit of a blur, I don’t know about you but I picture it full lockdown all the way. I was still at school then, and actually it was bits on, bits off. But in my head, it’s all off. Sitting around the flat watching shit TV, Jodie lying on the floor with Bobo, talking to him, telling him stories. She’d stroke his big, pink belly with the stretched-out spots all over it, brown and pink, and he’d go all stoned like, sort of purring like a cat except I never saw a cat slobber like he did. Or at all, now I think of it. Sometimes he’d stop purring and do this groaning whimpering thing, like Oh my god, too much, too good!

My thing with Bobo was more on a teenage boy level, like rubbing his ears really fast or getting him riled up with a ball — he was dozy, but a ball could get him going if you took the piss enough — then throwing it, seeing him run that big fat body as fast as he could, claws clicking on the pavement and he’d catch the ball high on the bounce, that was one thing he was good at, come back it would be all manky with slobber, not that I minded. I didn’t love him the way Jodie did, but we were mates. Bobber Slobber, was what I called him. She didn’t like that: thought it showed a lack of respect.

Anyway, the way I remember it, was lying around the flat, shit TV, sometimes walking Bobber but mainly bored, for months on end. Mum worked in the Tesco so she still had to go in, being an essential worker, but me and Jodie were both off school so when mum was at work I was looking after her, too. She was a sweet kid but how many sixteen-year-old boys do you know whose dream career is babysitting?

My dream career was DJing, like Uncle Sean. Or, now he was getting older, cousin Jude. You could hear him practising on his dad’s decks, blasting out the old-school jungle across the estate all through those sunny days, Spring 2020. Only April, but it was hot. Day after day of sun with the three of us cooped up in that little box flat, I’d get to going outside, if you can call a two-foot deep window ledge with a little metal rail outside, Henry Walk across the way, big 40-foot gardens, one in particular right opposite all overgrown with wild flowers, couple of apple trees all in white blossom, empty — there was an old geezer lived there before, died in the first wave, we saw him carried out to the ambulance with a plastic mask over his face and never come back — and I’d be getting deep in the music, trying to figure out when the mixes came, what Jude was up to with the decks and the effects and that, and then I’d go somewhere else, imagine sitting in the shade there under the apple trees, blazing up a joint, cold drink maybe, some comics from the library, all on my own…

Then one day I went out and looked across and the garden wasn’t empty any more. No one in it, not yet: just stacks of old furniture, weird stuff made of bamboo, plus a zebra-skin rug on the patio that looked so old and yellow it had to be real, and a stack of little spear things with feathers stuck on. I sat there for a while, thinking hello, and then she came out carrying, I swear, a rhinoceros head. Again: manky as fuck, had to be real.

She was straining all her strength to carry it, muscles standing out on her arms like little scrunched-up springs under the skin. All wet with sweat, too. She put down the rhinoceros head — she was wearing a pair of jean shorts and a sports bra — then she sat down on it and wiped the sweat up off her face and through her hair, short and dark and just that little bit curly. Sat there a minute or two, then went inside, came back she’d taken the shorts off, big glass of something cold in one hand, long, thin joint in the other. She took a big drink, then sparked the joint and lay back on the zebra skin. After a bit, the smell of the joint floated up to where I was — kind of a spicy burnt-sugar smell that went with the old furniture and feathered spears and bits of dead animals from far away.

So okay, you could look at me on my little budgie perch and her sprawling out on her evil villain zebra skin in the shade of her apple trees, smoking posh hash, and yeah: lockdown was playing out differently, there, for the two of us. Later on, mum would look out at her and talk about it like that. Point is, though, she was in her underwear all covered in sweat, she was fit, and I wanted the garden but I didn’t want it all to myself any more, from then on I wanted to be there with her. I wanted her. I mean, I was sixteen, and there she was, lugging out junk into the garden, loading it into the back of a car in the driveway alongside, driving off when the car was loaded full — I never knew where she took it all — but lots of the time when it all got too hot and sweaty for her she’d just lie there, bra and pants, blazing it up in the sun. Day after day.

When Jude was playing she’d sit up and do a little dance, arms and wrists, shimmying her shoulders and shaking her tits. She was good at dancing — natural — must have known people could see into her garden, see her dancing away in her underwear, but she didn’t seem to care. Maybe she liked it. I’d imagine it was me playing out, her dancing to my tunes.

Then summer came round for real, with the plague parties happening every week and Jude in the middle of the whole thing, and I saw what that was like close up.

***

I wasn’t in on organising the parties, of course: skinny younger cousin of the DJ, hanging round the edges, trying to pick up courage to talk to the girls, that was me. Obviously mum didn’t want me going, not so much because she was worried about the Covid, more the drugs and that. But by that time it was full summer, no school at all, dad gone, two kids to look after plus work and she was tired. I could sneak out the flat at eleven, she’d be dead and gone.

Those parties, man. I go to a lot nowadays, and I mean a lot, what with my line of work, but none of it comes close. Something about it being illegal: something about the night bus, finding your way from your stop way out North or East, the city so quiet at night in those days, you on your own, on a mission: then the walk through waste ground, the gap in a wire fence somewhere, disused warehouse, abandoned railway arch, one time an empty office block that still had all the shiny furniture on the first couple of floors… And then some of it was the people, everyone coming out from months locked up at home, and knowing how much it was supposed to be wrong and bad, and us going fuck it. No good party ever happened without a bit of that, a bit of fuck it.

Jude would be DJing, and he’d leave my name with the guys on the door when he remembered to. Otherwise you could usually sneak in. More fun that way: creeping from cover to cover like commandos, finding the back window, the way in across the roof, whatever. Once I was in, I’d find Jude, and where he was there would be pills, joints going round, girls — a few we knew from the Duchess, but all sorts of others, students, posh girls, older women, in their 20s and that. They weren’t interested in me, they wanted a piece of Jude and his mates, but: girls on pills, everyone loved up, dancing, eyes like flying saucers, sweaty massages… horny teenage me in the middle of all that, having the time of my life but I wanted to be Jude in that scene, behind the decks, everyone screaming when I dropped the big tunes.

I don’t remember when I first started going round Jude’s to practice. In my head it’s still summer. Round his place, there’d be a jostle around the decks, Jude’s older mates at the front of the queue. I did a lot of waiting around, and that’s what I was doing the day I first saw the claw, waiting for a turn on the decks, other people dropping in and out also wanting a turn, or wanting to buy a bag of weed or some pills, Jude not a serious dealer at that time but he always had plenty of gear what with the parties. The sun was slanting in hot through the little windows above where he had the decks set up, and when she came in it lit her up golden.

I’d never seen her close up before — this was the zebra skin girl, the Henry Walk sunbather, of course. She’d come to buy some pills. There was a queue, people sitting on mattresses on the floor, skinning up, one of Jude’s mates on the decks. She sat down next to me and started skinning up with that posh hash of hers. Made a long thin one, two Rizla end to end, and took four or five big drags before she passed it to me, quarter way gone already. I asked her what it was and she gave me a big smile and said, ‘Charas. It’s tainted with opium.’

That got some attention from the others there. She must have been coming round for a while already, everyone seemed to know her. Jude said, ‘What, you find that in your grandad’s stuff as well?’

‘Nah,’ she said, giving it the Duchess-type accent. Usually when a posh person did that it came across kind of pathetic, but with her it was different. The way she’d said, ‘tainted with opium,’ letting us know what she was, so that ‘nah’ wasn’t like sucking up to us. It was more like, the way it felt to me, like she was saying the world is a big place, highs and lows like you wouldn’t even know, and it’s not such a big distance between Henry Walk and the Duchess. You might think that’s a lot to get from one ‘nah’: but whatever the reason, she was right at home in that room, and pretty soon I could see that was about Jude, more than just buying pills. Jude was plague parties, inner circle, used to it by now but this girl was something else and he was loving it — serving her before her turn, chatting about what she’d turned up in that house, used to be her grandfather’s, now hers. He must have been really old, the grandad, because it turned out all that stuff was from India and Africa and places, when they were part of the British Empire or just after. ‘Colonial loot,’ she called it. Most of it she’d got rid of, but a few things like the zebra skin she’d decided to keep.

She had a shoulder bag, kind of World War Two-looking, brown leather gone all pale from the tropical sun, I imagined, with the initials V. F. on it, little gold letters stuck into the leather. There was more stuff inside, that she brought out to show Jude, others crowding in for a look, even the guy on the decks turning round to see. There was a hollow ball on a stick, all carved with patterns made of dots, a tuft of hair coming out where the stick joined the ball, rattled when she shook it. She said it was a witchdoctor thing from Africa. Jude started shaking it in time to the music coming from the decks, 4/4 at first then mixing it up, putting in a breakbeat, phasing 5/4, 7/4… he was good, she was loving it, and I was sitting back on the mattress letting the charas, tainted with opium sink in. The music, and the rattling, and the girl in the golden light moving to the beat. She wasn’t a girl compared to me, must have been a good seven, eight years older, but it was like at the parties: being there, being Jude’s cousin, I felt like part of the scene, even if I was just sitting there on the edge of it.

I must have been stoned, because after a while Jude threw a packet of Rizla at me and said, ‘Get those eyes back in your head, sonny boy,’ and everyone laughed. Took me a moment to realise I’d been staring at her, zoned out, for I don’t know how long. She was laughing too, but meeting my eyes, like I was in on it. She threw me her hash and baccy to go with the Rizla, said ‘Would you please skin up for me, young man,’ in a jokes-ladylike voice. Then she was reaching into the bag again, saying ‘Oh-oh-oh I forgot, new stash box new stash box.’

For a minute I thought she was bringing it out to show me, but, wrong: she turned to show it to Jude and I was sitting there with a dozy grin still on my face, looking up at the back of her head, then down as she brought out the box. It was some kind of metal, old, kind of dark and greasy-looking except for the gold patterns which I’m guessing were actual real gold — fiddly patterns of thin lines and corners repeating across the sides and lid.

‘Open it,’ she said, kind of mischievous, and Jude leaned in to work the little catch and then it sprang open and he sort of jumped back going Fuuuuck, man! and it fell out of the box — the paw, the foot, whatever, falling out in a little puff of rank-smelling dust — fell on the floor and bounced across to land up right in front of me.

Something about that bounce, I swear. I told you before what it looked like — dried-up roadkill — and what it did not look like was something that bounces. It had to get up off the lino, onto the mattress I was sitting on, too: and for that last bit, I know you’ll say I was high and that, but I swear for that last bit I saw it move, little skitter of the toes, claw clicking on the floor, like it was building up to the jump.

Everyone else was laughing at Jude, except me looking down at this manky item practically in my lap. Manky, except for the actual claw itself. That was shiny as the gold on the box except black, pure black, gleaming like a liquid, so smooth that I couldn’t help touching it just to see what it felt like.

‘No-no-no don’t,’ she said, and I looked up to see her staring at me, eyes wide like she wasn’t joking anymore. That was only for a moment, then she was grinning at me — which was okay by me, obviously — and saying, ‘Don’t touch it.’

People were still laughing, not sure what she meant but going along with it. Then she goes to Jude, ‘Read the note,’ and Jude looked in the box again and picked something out from the bottom. It was a piece of paper, not old like you’d expect, coming out of a thing like that, just lined white paper written on in biro. I’ve got it with me now. Not that I need to look anymore, number of times I’ve read it since then.

‘Go on, read it,’ said the girl.

‘14th September, 2019,’ Jude said, giving it some drama. Then, ‘To my darling V’ — looking at her, eyes wide on the darling: that was her, ‘V’, I never heard what it was short for — ‘this curio, which I bequeath to you knowing your penchant for whimsy, comes with some folklore attached. The man who gave it to me had served his time out East, in Burma, and told me it was imbued with what I suppose you would call a magic spell, by a fakir of his acquaintance.’ Jude was doing a whole voice for the grandad, who’d obviously written this, but he got ‘fakir’ wrong, pronounced it ‘faker.’ Not that I knew that then. Anyway, he went on, giving it the voice: ‘The story goes that the mummified bat claw herewith enclosed will grant three wishes to three separate recipients. My friend, wishing no doubt to make my flesh creep, told me that he had used it himself but regretted having done so, and warned me to keep it unused, but also to keep it safe, since destroying it would infallibly lead to the gravest of consequences. I have in fact kept it safe, more as a conversation piece than anything else. Perhaps it will find a home with you, or if you quite understandably don’t want it, with some antiquarian collection or museum.’

Jude was a bit out of breath by the end there, lot of effort gone into his posh grandad voice. V was looking around, still half grinning, but kind of thoughtful with it.

‘So who wants it?’ she said.

No one said anything at first, then they’re all crowding round, looking at the thing on the mattress in front of me — looking, but not touching — and all going like, ‘Nah man,’ or ‘That is rough,’ things like that. It was a manky-looking item, no doubt. Then they started joking around, saying what they’d wish for, or mostly what other people would wish for, taking the piss, like: Jude’s mate Paul said Jude would wish for a blowjob from Ellie Lourdes, which by her reputation you wouldn’t need a magic claw to wish for that, and then just after he said that he looked at V, who wasn’t laughing, and Paul went all red and there was a bit of a silence. And that’s when I heard myself say: ‘I’ll take it.’

Still don’t know why I said it. I mean, V was looking at me now, and that was part of it, but it’s not like everyone else in that room didn’t want her to look at them too, and none of them would even touch it. It’s not like I even thought, say something to make her look at you. It just came out.

‘You really want it?’ she said. Not laughing anymore — no one was — just looking at me, serious-like.

‘Yeah,’ I said: and she nodded, just once, slowly.

‘Ok, Jude’s cousin,’ she said. You might think, there, she didn’t even remember your name, you mug: but that’s not how she said it. More like, with respect: like, you’re not just Jude’s cousin, are you?

‘Keep it safe, though,’ said Jude, doing a woo-woo scary voice. ‘ “Since destroying it will infallibly lead to the gravest of consequences.” ’

‘What you going to wish for?’ said one of his mates, taking the piss again, looking sideways at V, but she still didn’t look like laughing.

And now here’s a couple of things I only found out later.

One: V’s mum and dad died, not long before her grandad. Car accident. That’s how this young girl ended up with this big posh house in North London, see?

Two: the accident happened mid-September, 2019. Round the same time as the note, and I’m going to say just after.

Three is something I didn’t find out, only guessed, but I know it’s true just as much as I know what happened next, to me and Jodie — what’s still happening to me now — is true. Picture it, right? V’s grandad writing that note, he’s got the bat claw out, he’s holding it — remembering the story, not believing the story maybe but fuck it why not? He makes a wish, for jokes, or maybe it just pops into his head, he doesn’t even think ‘I’m making a wish now.’ Maybe two wishes. Doesn’t matter what for. Whatever the wish is — probably something silly anyway since he doesn’t believe in it — doesn’t count for shit beside what’s coming next. And he doesn’t know any better. Should’ve listened to his mate from Burma. I say maybe two, not three wishes, because I reckon he used his third about six months later, hearing about the new disease from out East, killing off old geezers like him by the thousand. Take me. Let it take me.

Of course, I didn’t know any of that, then. What I did know was, she was looking at me, noticing me. And that’s what I’d said it for, I guess. But even then, I didn’t want to do any wishes, not even for a laugh. Something about the way it bounced up at me from the floor, and something about the way it felt, the claw, when I touched it: it was cold, and just as smooth as it looked, like polished glass with a wicked sharp point on the end – and just when I was touching the point it seemed like it twitched, just the tiniest bit, tiniest prick of the point against my finger, not even close to breaking the skin, not even close to hurting. More like, hello. Of course, at the time, I said to myself all of it, the bounce, the twitch, was just me being a bit stoned — but at the same time I didn’t feel like messing with it.

I took it home, though, the paw and the note, in a baggie along with three pills and a couple of buds that Jude let me have. Put the baggie in a sock, in the toe of the pair of old trainers under my bed where I hid stuff like that, and that was that for the moment.

***

Next thing, about a week later, I was out on my budgie perch, mum at work, Jodie inside with Bobber, me wondering if V was coming out today — she’d kept up the sunbathing even though she’d finished clearing out the house, kept the zebra rug too, it was there in the garden waiting for her — and I was wondering if it would be weird of me to watch her there now, now we sort of knew each other. Or if she’d notice me watching, or maybe she already had, and I just didn’t know because she was usually wearing sunglasses. The things you worry about.

Anyway, then Jodie got bored and started whining at me to play with her. I didn’t mind, although some of the games she got me playing with her in those days were pretty embarrassing, like: mums and dads, Bobo being our kid, which was more embarrassing for him to be honest, the way she’d make him wear little hats she made out of her T-shirts, tied up under his chin. Poor old Bobber Slobber. You could tell he knew how he looked at those times. Funny thing was how much I could get into it: little bit stoned, making up stories with Jodie, messing with Bobo. No one else would ever know, so who cared if it was embarrassing?

So that’s what we were playing that time, and Jodie went off to find stuff to be sleeping bags for these little toy bunnies she had, were meant to be our babies. She was using mum’s socks for the little ones, but there was a bigger one that didn’t fit and I guess she must have been looking for some of my socks, me rubbing Bobber on the belly and not thinking about her poking around in my room. Anyway, she came back with the baggie, asking what’s this, knowing it was something as soon as she saw me sit up fast, me grabbing for it and then her running away and saying she’d tell mum. That got me pissed off, but I kept a lid on it, thought fast, and said, ‘It’s a magic claw. Give it here, I’ll show you.’

It worked, hundred per cent. Once I’d got the bat paw out and started telling her the story, she forgot about the rest. At the time I thought, Jesus, what if she’d taken one of the pills, they look enough like sweets. I suppose she’d have spat it out as soon as she tasted it. Anyway, they were all there and like I said, she forgot about them and the weed, I slid them into my back pocket half way through reading her the note, thinking yes, result: out of danger.

So then she asks me about the wishes, like, was it only me who got to make them? I was still thinking, keep her on this, so I tell her no, I could share the wishes with her. Next thing, she’s holding it, eyes shut, going ummm, ummm…

I wanted to stop her then. I was fucking terrified, to tell you the truth: all of a sudden, like stepping out into the road without looking and then there’s a bus about to hit you, whoosh, out of nowhere. I almost did it, but then there was the normal, sensible part of my brain telling me if I grabbed it off her there’d be a whole fight and she’d probably end up telling mum about everything, plus don’t be a mug it’s just a story you’re playing a game here and all that. Nice little game, forget about the baggie, move on. Even so, I almost did it.

Then she screamed and threw it down on the floor, staring at me eyes wide open and saying, ‘It moved!’

Bobber was up on his feet, staring at Jodie, staring at the thing on the floor, little whining sound coming up out of his big fat throat. I could feel my heartbeat, thump thump in my chest, massive, like pumping up a football inside there, bigger and bigger with each beat. I felt sick. Normal brain on holiday now, although I guess not entirely because what I said was: ‘Nah.’

‘I swear!’ She’d looked scared, that first moment, but now it was changing to fucking delighted. ‘It’s real, isn’t it?’

Whichever part of my brain it was controlling my mouth kept going. ‘What, d’you make a wish then?’ it said.

‘Yes.’ Eyes all shining like. ‘I made it, and that’s when it moved. It’s real magic.’ Her being at the age, see, when she was starting to doubt all that but only just starting. Like, the year before, she had this ‘wishes and dreams’ notebook, was obsessed with it, writing in it all the time, little drawings of what she wished for, and I hadn’t seen that in a while but in her mind it was still live: and now she was coming back down hard on the side of yes, for real, my wish shall come true.

‘What you wish for?’

‘If I tell you it won’t happen.’

‘Nah, doesn’t work like that. This doesn’t. It’s a different kind.’ She was nodding, totally believing me, like I knew all about it. Of course she was: I’d got the magic wishing claw, shared it with her, big brother never seemed bigger than right then. I reckon that was the moment I started feeling angry as well as scared shitless. Angry because I was scared shitless, and there she was, trusting me. I’d been pissed off, her poking around my stuff, finding the baggie: but this was a whole different level.

‘Okay,’ she said, ‘I’ll tell you. She leaned forward, grinning all over her face. ‘A light-up scooter.’

Can you blame me, that I lost it with her? I mean, yes: and I do. Poor little Jodie, that was the biggest thing she could think of. But on the other hand, one: I was already fucking scared, plus angry, and two, mixed in with one: I knew it was real. Like, deeply knew. Three wishes. Fucking light-up scooter. So it all came out, like the football in my chest bursting, bang: I was shouting at her, saying you could have anything you wanted, anything in the world, those were my wishes, you could have the fucking world and you waste it on that? Jodie started crying, of course. Bobber jumped up and ran out the door, I heard his claws going click-click-click down the passage outside, me thinking I swear the front door wasn’t open, and that same part of my brain that’s still somehow doing normal mode is thinking: so much for nice little game and move on, you’ve fucked it now sonny boy.

I guess normal mode made me stop shouting at her, normal mode made me give her a hug, or try to, she wasn’t having it at first, ran away and locked herself in the toilet. She came out in the end, and this is the worst: she was sorry. She thought I was right: she’d wasted one of my wishes and she was sorry.

Well. I felt bad about that, obviously. Not nearly bad enough, looking back. If I’d known what she’d do about it.

But I didn’t.

So.

I stopped being angry with her, anyway. Tried to cheer her up, like: there’s still two wishes left, plenty we can do with those, think it through properly and in the meantime you’ll have a light-up scooter! She stopped crying at least, went off to her room to do some drawing, she said. After a bit I could hear her singing to herself and reckoned maybe she’d got over it, maybe she wouldn’t make a fuss. Normal brain again, still worried about the weed and pills, what she might say to mum.

Then the rest of my brain, the part was keyed in to what was actually going on, looking at the claw lying there on the floor and knowing I should pick it up, put it away, but too scared to do it.

***

Five minutes, maybe ten, I sat there doing fuck all. Not that there was anything I could have done at that point, I reckon. Anyway, maximum ten minutes later I hear footsteps outside, coming up fast to our front door, not click-click-click this time but squeaking of trainers and then Jude’s there, all sweaty, red in the face, telling me I’ve got to come right now, it’s Bobo. I went to get Jodie, but he told me no, leave her, and the look on his face he didn’t have to tell me twice. I locked the door behind me and followed him down. Walking through the estate, past the little playground in the middle, he’s telling me it was a car, it looks bad — really bad — then we’re out on the Essex Road and I saw the car stopped, big black Audi, hazard lights on, whole crowd of Jude’s mates surrounding the guy who’d been driving, they’d got him backed up against the side of his car shouting at him.

At first I couldn’t hear Bobo because of all the shouting. I was heading for the guy, Jude telling his mates he’d found me, and they all quietened down and that was when I heard it: that same kind of groaning sound he did when we scratched his belly, deep breaking to high pitch, like too much, except now it wasn’t too good anymore. I never heard anything like it except once since then. People talk about humans sounding like animals, like me saying that Sainsbury’s woman sounded like a cat — and it’s meant to show that they’re totally off the deep end, right? Except we are animals, and the noises we make aren’t so different, like I could always tell where Bobo was coming from when he made that noise, or the little wheep-wheep noises he’d make when I was playing ball with him, getting him riled up.

This noise was coming from somewhere else, somewhere beyond: somewhere I never wanted to know about. But then I saw him, front half totally normal, then his belly and the part of his back above it smeared across the road, burst open, leaking tubes and blood and shit — then his back legs, arse and tail, stretched out beyond the mess, one leg still kicking a little — and the sound matched the sight, that was where it was coming from, what it was like to look like that and still be alive.

No one was looking at him, because why would you want to? Everyone was looking at the guy, getting angry instead of whatever it is you’d feel from looking at Bobo, the state he was in. But he’d seen me — recognised me — and we were mates, so here comes the one good thing I did in this whole sorry story.

I still had the baggie in my back pocket. I walked over to him, fiddling it open. Spilled the gear back in my pocket. It was a big baggie, big enough to fit over his muzzle. I gave him a scratch behind the ears with one hand, him panting up at me, eyes looking like sorry, mate, I’m not up to playing ball right now, you see the problem — while I crammed the baggie over his snout, holding his jaws shut, him too weak to struggle. I remember the plastic going tight over his snout like shrink-wrap. Me still scratching behind his ears, hard as I could, crying now. It didn’t take long. Afterwards everyone was staring at me, all the fight gone out of them. Audi guy took his chance then, to get away clean: peeling off twenties and fifties from a roll he’d got out of his car, giving them to me, everyone standing round looking solemn, and then he was off. I’ve wondered about Audi guy, since: ninety-nine per cent he was a dealer to have that kind of cash on him — and it was only part of his roll — cheap at the price, if so, for him to get away without any more attention. And no coincidence, I know that for sure, that it was him hit Bobo, able to give us the money, so that things would turn out the way they did.

Jude was good, him and his mates. They helped me get Bobo up off the road, wrap him up so you couldn’t see all the mess. I knew Jodie would have to see him, but no way was she going to see all of it.

I went up by myself to tell her, left Bobo down by the playground with Jude, people stopping to ask what had happened. She didn’t ask why I’d left her locked in alone, didn’t seem to mind it — in fact, she was smiling, like she had some secret she wanted to tell me — and then I told her, and her whole face crumpled up just like that.

I was worried about the smell, what with all that stuff leaking out of him, but by the time I got her down to see him she was all snotty with crying, nose blocked up and streaming down her mouth. She was hugging his head, talking to him, telling him not to be dead. Like I said, she was that age where she still thought it might work, telling him over and over, stroking him and that. Pulled one of his eyes open, told me look, he’s looking at me, he’s coming alive again.

We buried him that night in the woods bit, far side of the river in the Henry Walk park — got in through a gap in the railings we used to go in through to blaze up, nights, when it was closed. I should say, mum came home before that: she was angry with me for letting Bobo out like that, and at first she was angry I’d let Audi guy go without getting his details but then I showed her the money and she took it, getting quieter while she counted through it. Must have been five hundred quid there, maybe more.

Another thing: the bat claw was gone from the floor. I never thought about it when I was going up to get Jodie, take her down to Bobo, but when mum got back I thought fuck, she’ll see it — but it was gone. I checked later and it was back in my old trainer under my bed, along with the note. Freaked me out at the time, thinking it got back there by itself I suppose — I don’t know what I was thinking, actually, just generally miserable and scared and guilty — although I never guessed what really happened until much later.

Jodie got very serious about the funeral. Still crying pretty much non-stop, but mum took her to a posh florist’s to get a bouquet, and then she was picking other things to bury along with him — his favourite ball, the T-shirt she used to put on his head she said he liked the most, that kind of thing. I won’t say it cheered her up, but she was calmer.

Calmer, maybe, but still grieving. She loved Bobo more than mum or me, and everyone knew it. That’s why mum used the money — a part of the money — to buy her the one thing we all knew she wanted. Three days later, she came back late from work, had stopped by Argos on the way home, lugged the big box up the stairs and told Jodie, ‘Surprise!’ It was no surprise to me, as soon as I saw the box I knew what it was. When Jodie saw it, I don’t know what mum was expecting but it wasn’t this: screaming and crying, running to her room, wailing about Bobo, mum looking at me like what did I do?

I knew. Josie’s wish had come true, just like she knew it would, and the price was Bobo being dead. She got it. She was sharp, like I said. She never used that scooter. Not that she had long to come round to it.

Next few days, mum knew something was bad, badly wrong, but what could she do? Out to work in the morning, coming back knackered, meantime me and Jodie sitting around, Jodie wouldn’t say a word to me. Blamed me, maybe, for letting her make that wish in the first place. Fair enough. Fair enough.

Then, about a week later, she perks up, all of a sudden. One moment sitting there watching TV, the next she’s looking at me like a light’s come on inside her.

‘The claw!’ she said.

I must have looked confused, because the only way I thought she’d mention the claw to me was like, fuck you, you showed me the claw and now Bobo’s dead. But she was smiling all over her face.

‘We can wish again,’ she said, and then I knew what she was getting at, or at least was beginning to because I started shaking my head.

‘Nah, nah, Jodie…’

‘We can make him come back to life.’

‘What, after this long?’ And she hadn’t seen him in the road, either.

‘It’ll work. It’s magic!’

‘What, like it worked before?’ But she was up already, quicker than me. I chased her but she was quick, got to my room and dived under the bed and came out with it clutched in her hand, already whispering.

‘Fuck, Jodie,’ I said.

She finished her whispering and grinned at me, a half-mad sort of grin. ‘Don’t swear,’ she said. Then, ‘It’s working already. I felt it move.’ She was still holding it tight, like I might try and take it back off her, reverse the wish. I didn’t want to get near it, to tell the truth. ‘You’ll see,’ she said. ‘He’ll come back.’

She never doubted it, never doubted it would be fine. I was getting that big feeling in my chest again, only not sudden this time, no whoosh! but slow, building up beat by beat.

‘Put it back under the bed,’ I said. And she did. And waited, sat around the rest of that day with a little smile on her face, waiting for Bobo. Mum came back, said something like you’re looking better, and Jodie just smiled that secret little smile at her.

Nothing happened till late that night. It was quiet, everything closed because of the Covid I guess. Quiet streets, quiet city, but I couldn’t sleep. I was waiting, just like Jodie, or no: not like Jodie at all, because I knew what we were waiting for. I remembered the way Bobo looked there on the street, back half smeared across the tarmac, leaking, and the sound coming out of him, coming from a place I never wanted to know about.

Quiet, anyway, so when I heard it coming it was clear. Click-click-swish. Click-click swish. Coming along the passage outside, getting nearer and nearer to our front door. A wetness to that swish, like a mop dragged all sopping across the floor. I heard the sound of Jodie sitting up in bed in the next room. Then I heard the sound from outside, right outside the door, a groaning yawning sound going low to high pitch, ending in a little gurgle, like too much — too much of something I never wanted to know about, coming from a place I never wanted to think about — and then it went low again, a snuffling sound that made me think of big teeth and loose lips and a tongue drooling blood and shit and fuck knows what else.

Bobber Slobber.

And then Jodie’s feet were running to the door, I was out of bed, knowing I was too far behind — her room was closer to the front door and she knew how to undo the latch herself, she’d learned how to do that a couple of months before, was always showing off about it — and then it came to me, bam, genius, one wish left, and I was under my bed scrabbling for the old trainer, hand inside, grasping the claw, wishing, scared shitless, knowing it was going to squirm in my hand and for some reason more scared of that than whatever was outside, but:

Nothing.

No squirming. No prick of claw against my skin. Nothing, except the sound of the door opening, and the snuffling getting louder, and Jodie saying ‘Bobo,’ just for a tiny moment overjoyed before the screaming started.

***

Nothing much more to say. I saw her body, afterwards. Mum standing there beside me making a whole other type of noise I never want to think about. I thought it was bad, what a car can do to a dog, but what a dog can do to a little girl is worse. I won’t say any more about that.

I didn’t see the thing that did it, the click-click-swish thing that used to be our dog. Mum was first out, and she must have beaten it down. Too late for Jodie. By the time I got out there, Bobber was as dead as ever. Mum never talked about how come he was there, how come he did that. No one did, at least as far as the ‘dog coming back to life a week later’ part goes. ‘Dog kills little girl’, that part went as you’d expect. In the news, campaign about killer dogs, all that. What gets me is, so many people saw him dead first time round and no one said a word about it. Like that part of it never happened.

Not long after, dad was back. I didn’t see him. Heard him, though — late in the night, again, shouting at mum, everything all her fault — slaps and then heavier sounds and then he was gone, door slamming, swearing and weeping getting quieter as he went. I stayed in my room. Want to say I went and comforted her, then or later, but the truth is I was zero comfort to her at all. I was gone, far gone. So was she. Nothing to say to each other. She let things slide, lost her job, started doing a lot of Valium. I moved out, basically, ended up sleeping most nights on the mattress in Jude’s living room. Jude was good about it. Eventually he cleared out a little bedroom for me, more of a cupboard than a room: it had the boiler in it, and my mattress, and the decks.

Yeah. The decks. He’d got some new ones, digital, and he and Uncle Sean agreed to give the old ones to me. Because of what happened, of course. Dream come true, or would have been before. After the claw, they were even more than that. After the claw, the only way I could stop thinking about Jodie, about the sounds and the screams, about what I’d done to her? Was smoke a joint, get on the decks, get lost in the music. And I mean lost: people say that and they don’t even know: but I went deep. I had to, to get away from it. I’d go places in that tiny little room, headphone in one ear, monitors cranked right up, I’d see colours in the music, make patterns that weren’t there before, hours and hours where I forgot everything except that.

People noticed. Mates of Jude’s, not everyone who came round was there to buy pills or just smoke a joint or whatever. One time, a mate of his, another DJ, said I should be making mixtapes and brought round an old cassette recorder. It was tech, that recorder: different inputs, high precision, you could splice bits of a mix together, make loops, all sorts. After I learned how to use it I swear I never came out of that cupboard except to empty my ashtray. Boiler room freak, cassette boy goblin, that was me. Months like that. The first time I heard one of my mixes played out on the radio I didn’t even think it was weird, because just being out in the sitting room for more than five minutes was so weird already.

Uncle Sean arranged that, with a mate from his pirate days who was still a radio DJ. It was Jude who got me playing out at clubs and parties: from about a year later, that was. And apparently the stuff I’d been doing with the cassettes meant I was a producer as well — not just a producer, but a ‘new breed’, an ‘innovator,’ whatever else people wanted to call me to show they got the new sound and were down with it, and believe me they wanted to show they were down with it. Radio people, party people, club people — girls, women, oh yes. Everything I ever wanted, from before. Nowadays I get paid in cash, off bigger rolls than Audi guy could ever dream of. Except when it’s radio money, which comes in checks through the post. Or streaming money, which comes straight into my bank account. Given percentage funnelled off into another one, to cover taxes. I just moved up a bracket.

All a bit suspicious, right?

Through it all, I was head down, basically still in the boiler cupboard, staying stoned and in the music. People love all that. It’s my image. Sometimes I’d go days without thinking about Jodie. The question that always brought it back, though, the first year or two at least: why didn’t it work? When I made that third wish, to make the thing outside our door go away, the click-click-swish, slobbering thing that killed my sister: why didn’t it work? Wish number one: light-up scooter. Wish number two: bring back Bobo. Wish number three: Bobber Slobber go away.

Except: no. Because number two, there? Wasn’t number two.

Mum was on her own in the flat after I left, dad being gone for good, me being gone for the foreseeable, and then Jodie. So just mum, then. Not like she wanted to stay there, and of course the council wasn’t going to keep her there either, three bedroom flat. Took a while for all the wheels to turn, but around 2022 I got a message from her saying she was moving out, and did I want to pick up any of my old things? I ignored it for about a week and then just turned up. No emotional reunion — I don’t know if that was what she was after — maybe one day, but not then and not yet. I did go into Jodie’s room, though, have a look, think about her. Don’t know why, seeing how I’d spent going on two years doing everything I could not to think about her. That fucking scooter was there in one corner, still in its box, but that’s not the point. Point is, I was looking through a pile of her drawings and stuff, and I found her notebook: the Wishes and Dreams book, with the unicorns and hearts on the cover. Soon as it was out of the pile, it fell open to the last page she’d written on. Months after the rest: it was from that afternoon that Bobo died, and it wasn’t just writing, she’d done a drawing too. I remembered, after me shouting at her, she’d gone to her room and said she was drawing. There was the scooter, all crossed out with deep angry lines. Then there was a picture of the claw, with magic wavey lines and stars coming out of it. Then there was me, she’d done a good job of me, she was always good at drawing — me playing out on the decks, people dancing all around, some kind of princess looking up at me with love hearts in her eyes. Wish Number Two. The writing said: ‘Everything in the world he wants.’

She must have come down after I left with Jude, picked up the claw to make it official, then put it back in the trainer under my bed. It was still there. I took it with me that day, the claw and the note. I’ve read through it again since then. Three wishes to three separate recipients, it says: so it should be dead now, all the magic used up, Burma guy, then V’s grandad, then Jodie. But then there’s that bit about not destroying it, and the dire consequences — and the claw still gleams, I’ve got it out now and it still has that weird shiny thing going on, like black ink holding together into a solid shape. And it still feels cold to the touch.

I’ve kept it, I guess because I don’t want some poor mug to pick it up and then let it get destroyed and then get cursed or whatever. That’s the reason I tell myself most of the time. Meanwhile I’m the guy who’s got everything in the world he wants, letting it wash over me, trying not to think about it too much and, to tell the truth, a lot of the time I’ll manage that.

Sometimes I’ll take the claw out and look at it and think about V’s grandad, wishing for death in the butt-end of winter, 2020. And think about destroying it myself. The direst of consequences.

Yeah. Sometimes that sounds about right.